Tax Tips For Investors - 2024 Addition

BMO Private Wealth - Nov 08, 2024

Knowing how the tax rules affect your investments is essential to maximizing your after-tax returns.

Knowing how the tax rules affect your investments is essential to maximizing your after-tax returns. Further, keeping up to date on changes to the tax rules may open up new opportunities, or could affect how your financial affairs should be structured.

The 2024 edition of Tax Tips for Investors provides ideas that you may incorporate into your wealth management strategy. As always, we recommend that you consult an independent tax professional to determine whether any of these tips are appropriate for your particular situation and to ensure the proper implementation of any tax strategies.

Tip 1: Reduce Tax with Income Splitting

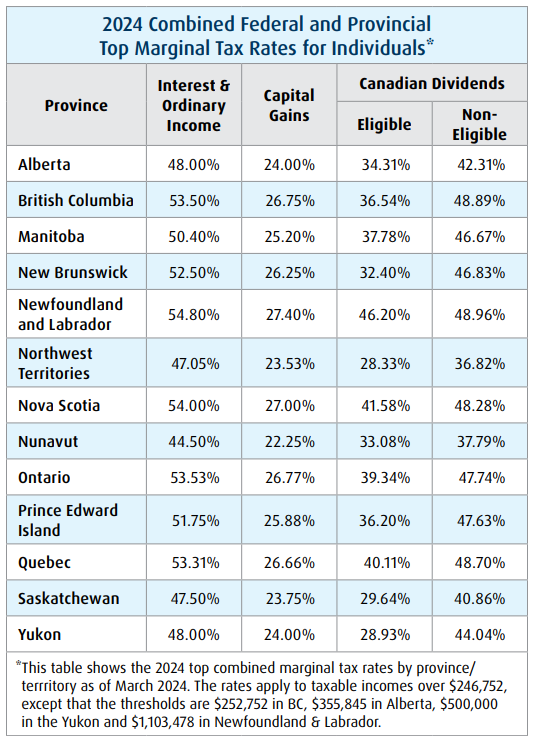

Under our tax system, the more you earn, the more you pay in income taxes on incremental dollars earned over specified threshold levels. With this in mind, it makes sense to spread income among family members who are taxed at lower marginal rates in order to lower your family’s overall tax burden. However, the income attribution rules can prevent most Income Splitting strategies where there has been a transfer to a spouse or minor child for the purpose of earning investment income. The attribution rules re-allocate the taxation of investment income (and capital gains in the case of a gift to a spouse) to the person who made the gift regardless of the name on the account in which the investment is registered. In addition, the recently expanded tax on split income, or “TOSI” rules, discussed in the “Tax Planning Using Private Companies” section, will also impact the ability to income split with family members. While there are significant restrictions, there are a number of legitimate Income Splitting strategies available to you. In light of high top personal tax rates (see chart on page 13), these strategies will have greater importance for families with disproportionate incomes.

Loan at the prescribed rate

An interest-bearing loan made from the person in the higher marginal tax bracket to a family member in a lower tax bracket for the purpose of investing provides an Income Splitting opportunity. However, it is important to note that there are a number of requirements that must be met. For example, interest must be charged at the Canada Revenue Agency’s (“CRA”) prescribed rate, effective at the time the loan is made, and interest for the previous year must be paid by January 30 of each year. The CRA sets the prescribed interest rate quarterly, based on prevailing market rates. Periods of low prescribed interest rates are generally the best time to establish a loan since the low rate can be locked-in for the duration of the loan. In order for there to be a net benefit, the annual realized rate of return on the borrowed funds should exceed the annual interest rate charged on the loan, which is included in the income of the transferor and deductible to the transferee family member if used for investment purposes. Any potential impacts of increased income to the transferee family member (i.e., loss of spousal tax credit) should also be considered before employing this strategy. Finally, it is important to consider the possible recognition of capital gains or capital losses (which may be denied) when assets other than cash are transferred or loaned to a family member. However, as the prescribed rate increases, the Income Splitting benefit narrows. Based on the recent increases in the prescribed rate, long-term benefits of income splitting will only be achieved to the extent that future investment returns exceed the higher rate thresholds. As such, the strategy may no longer be beneficial for most taxpayers, unless sufficient funds are advanced and there is a significant discrepancy in marginal rates between family members (depending on the amount and nature of investment income earned on the loaned funds).

Income Splitting with a spouse or common-law partner

Income Splitting with a spouse or common-law partner (hereinafter referred to as “spouse”) can be achieved with a prescribed rate loan, or in a number of other ways. For example, the individual earning the higher income (who pays tax at a higher marginal rate), should pay as much of the family’s living expenses as possible. This allows the lower-income spouse to save and invest their income. The earnings on those invested funds will be taxed at a lower marginal rate and the overall family tax burden will be reduced. Income Splitting in retirement can be achieved by making spousal Registered Retirement Savings Plan (“RRSP”) contributions while working, through pension Income Splitting and by sharing Canada Pension Plan (“CPP”) / Quebec Pension Plan (“QPP”) benefits. See further details about “Spousal RRSP” on page six and “Pension Income Splitting below”. In addition, since the introduction of the Tax-Free Savings Account (“TFSA”) in 2009 (see page 6), funds can be provided to a spouse (or adult child) to allow them to contribute to their own TFSA, subject to their personal TFSA contribution limit. Since the income earned within a TFSA is tax exempt and is not subject to the attribution rules, a TFSA provides a simple and effective Income Splitting tool. However, care must be taken if assets other than cash are gifted to a family member to fund their TFSA contribution.

Pension Income

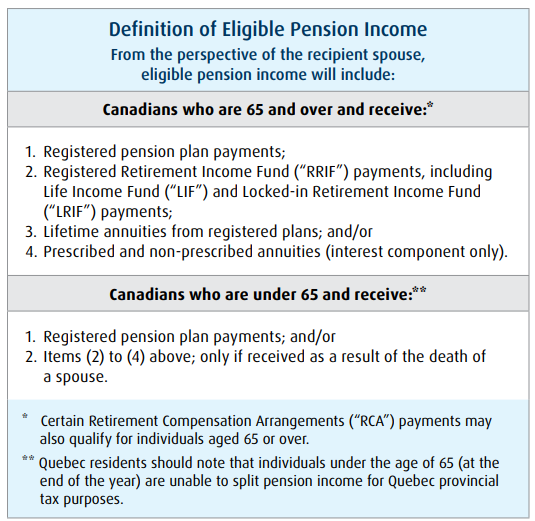

Splitting The pension Income Splitting legislation allows a transfer of up to 50 per cent of eligible pension income to a spouse, which provides a significant opportunity to split income where retirement incomes are disproportionate. The allocation of this income is done by each spouse making a joint election annually in their respective tax returns.

For income tax purposes, the amount allocated will be deducted from the income of the individual who received the eligible pension income; and this amount will be reported by the other (lower income) spouse. The definition of eligible pension income is similar to the definition used for determining the eligibility for the $2,000 pension income tax credit, such that individuals currently eligible for this credit will generally be eligible to split pension income with their spouse. See the Definition of Eligible Pension Income below. Please note: It is the age of the spouse who is entitled to the pension income that is relevant in determining the eligibility for pension Income Splitting, such that it is possible to allocate eligible pension income to a spouse under age 65.

Income Splitting with adult family members

In making a gift to adult children or other adult family members, you will not likely have any control over how the funds will be used. However, a gift may allow them to make an RRSP or TFSA contribution or give them an opportunity to earn investment income at their lower marginal tax rate. In addition to adult children or adult grandchildren, you may want to consider this strategy for parents whom you otherwise support in after-tax dollars. The attribution rules do not generally apply to an adult relative (other than a spouse) if a gift is made. However, these rules may apply in a situation where a loan is made to a related adult where no interest (or interest below the prescribed rates) is charged on the loan, if one of the main reasons for making the loan is to split income. As previously mentioned, it will be necessary to consider the possible recognition of capital gains, or capital losses (which may be denied), when assets other than cash are transferred or loaned to a spouse or other family member.

Income Splitting with family members under age of 18

If structured properly, Income Splitting can be achieved by making a gift to a minor child – typically through a trust structure – to acquire investments which generate only capital gains. In most cases, capital gains earned after the transfer of a gift can be taxed in the minor’s hands. However, interest or dividend income will attribute back to the transferor parent unless fair market consideration (such as a prescribed rate loan) is received. In addition, second generation income (i.e., income earned on income from the original gift) does not attribute back to the giftor. Any income earned on contributions made for a child in a Registered Education Savings Plan (“RESP”), is taxable to the child when withdrawn for education purposes (see “Tip 5” on page 8). Income Splitting strategies with minor children, particularly when considering dividends from a private corporation or earnings from a business involving or owned by family members, may not yield the intended tax advantages due to the application of the “kiddie tax” regulations. These regulations mandate that income received by minors under these circumstances is subject to taxation at the highest marginal rate, foregoing the benefits of lower, graduated rates. This mechanism is designed to discourage the shifting of income to minors for the purpose of tax minimization. Notably, as we delve deeper into the topic in the subsequent section, it’s important to recognize that, starting in 2018, the scope of these rules has broadened to potentially encompass family members of any age.

Tax changes impacting private companies

Tax legislation affecting planning strategies involving private corporations was enacted several years ago. Strategies involving private corporations which were specifically targeted by this amended legislation include:

- Income Splitting: In light of changes to the “tax on split income”, or “TOSI” rules, effective for the 2018 and subsequent taxation years, any shareholder of a private corporation who does not meet specific exceptions will be subject to these expanded TOSI rules which apply the highest marginal tax rate to income, including dividends, paid to them directly or through a family trust. For more information, please ask your BMO Private Wealth professional for a copy of our publication, Tax Changes Affecting Private Corporations: Tax on Split Income (“TOSI”).

- Holding passive investment portfolios inside a private corporation: Two measures introduced in the 2018 Federal Budget may also impact private companies that earn active business income either directly or through an associated corporation. The first measure enacted limits access to the Federal small business deduction (“SBD”), where the corporation or associated corporations earn significant passive investment income. The second measure enacted restricts the ability of a private corporation to recover refundable tax on investment income earned, in certain circumstances. Please ask your BMO Private Wealth professional for a copy of our publication, Understanding Personal Holding Companies for more information on these important changes.

Tip 2: Make Your Portfolio Tax-Efficient

There are numerous investment options available today, each with their own investment merits and many with unique characteristics. As an investor trying to determine the most appropriate investment strategy for your portfolio, it’s important to consider the level of risk associated with the investment and its expected return. When evaluating returns you should consider the impact of income taxes, since not all investment income is taxed in the same manner. Despite the wide range of investments available, there are three basic types of investment income: interest; capital gains; and dividends. Each of these is subject to a different tax treatment. Interest income is taxed at your marginal tax rate. However, if you realize a capital gain, you only pay tax on 50 per cent of the gain. By including only 50 per cent of the capital gain, the actual tax you pay is lower than if you had earned the same amount in interest income. Some investments distribute a return of capital (“ROC”) which is not taxable upon receipt. Instead, the ROC reduces the adjusted cost base of your investment which will impact your gain or loss on the ultimate sale of the investment. Special tax treatment through the Federal and provincial dividend gross-up and tax credit mechanisms exists for dividends paid by a Canadian corporation to a Canadian individual investor. Specifically, lower effective tax rates apply to “eligible” dividends, which encompass distributions to Canadian resident investors from income that has been subject to the general corporate tax rate (i.e., generally, most dividends paid by public Canadian corporations). Dividends received, which are not “eligible” dividends are subject to higher effective tax rates. Please ask your BMO Private Wealth professional for a copy of our publication, Eligible Dividends for more information on the taxation of dividend income.

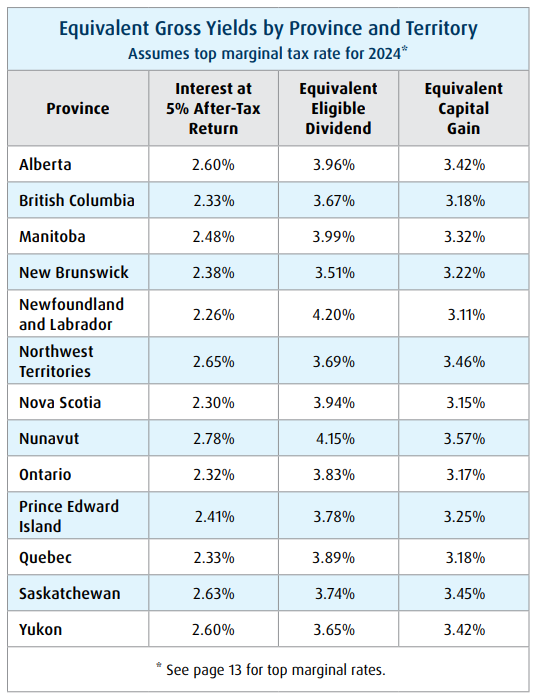

The table on page 13 provides the combined top tax rates by province and territory on the various types of investment income. Based on these rates, the following table illustrates the approximate pre-tax rate of return, by province/territory, for eligible dividends and capital gains that will result in the same after-tax return as earning interest at five per cent.

If a regular income stream is your primary investment objective, rather than interest-bearing securities, you may want to consider investing in preferred shares of Canadian corporations – which pay dividends that will be taxed at lower rates. However, keep in mind the potential impact that the gross-up on dividends can have on your taxable income and any income-based benefits (such as Old Age Security).

When deciding how to invest your registered (i.e., RRSP) and non-registered portfolios, consider holding interest-bearing securities in your RRSP, and investments that generate Canadian dividends and long-term capital gains (or losses) outside your RRSP. All sources of investment income earned in an RRSP are tax-sheltered until withdrawn, but all withdrawals are taxed at your marginal rate for ordinary investment income such as interest.

Many fixed income investments pay regular interest at set dates throughout the term of the investment. However, compound interest investments (such as strip bonds or GICs) pay interest only upon maturity. For tax purposes, the difference between the purchase price and the maturity value of these investments is considered interest income.

With compound interest investments, even though you do not receive regular interest payments, you must include the amount of interest “earned” each year on your annual tax return. This can result in a negative cash flow if the compound interest investment is held in a non-registered plan. If your investment strategy includes compound interest investments, it may be more appropriate to hold these investments in your registered accounts (i.e., RRSP, RRIF or TFSA), since you will not be responsible for paying tax on the income until it is withdrawn from the plan.

Tip 3: Maximize Your Tax-Deferred Savings with an RRSP or TFSA

Your RRSP is likely the cornerstone of your overall retirement strategy. Contributions to your RRSP are tax-deductible and thereby reduce your taxable income. In addition, the income earned in an RRSP is not taxed until it is withdrawn, which means that your savings will grow faster than they would if held outside an RRSP.

Maximize contributions

The maximum RRSP contribution that can be deducted in a particular year is available on your prior year’s Notice of Assessment from the CRA. Otherwise, to estimate your contribution limit start with any unused RRSP contribution room from prior years (accumulated since 1991), and add 18 per cent of your prior year’s qualifying “earned income,” up to the current year’s maximum deduction limit; $31,560 for 2024 ($32,490 for 2025). If you are a member of a Deferred Profit Sharing Plan (“DPSP”) or Registered Pension Plan (“RPP”), you must deduct your pension adjustment (and net past service pension adjustment, if any) when calculating your RRSP contribution room. If you leave your employer before retirement and lose the value of benefits under an employer-sponsored DPSP or RPP, a pension adjustment reversal may be available which restores contribution room lost because of previously reported pension adjustments. Contributions to an RRSP in excess of your maximum contribution room will result in a penalty tax of one per cent per month, if these cumulative “over-contributions” exceed $2,000.

Contribute securities

If you do not have enough cash to maximize your RRSP contribution, consider transferring securities you already own to your RRSP. This is called an “in-kind” contribution because property, not cash, is contributed. Securities include stocks and bonds of publicly-traded Canadian corporations, and bonds issued by the Federal and provincial governments. The amount of the deductible contribution will be the fair market value of the property on the date of transfer. You will be required to report any capital gains accrued to the date of transfer on your tax return. Avoid transferring assets with accrued capital losses since a capital loss realized on this transfer is denied for tax purposes.

Use a Spousal RRSP

A Spousal RRSP is the same as a regular RRSP except that it is registered in your spouse’s name, allowing you, as the contributor, to take a tax deduction for your contributions made to the plan. When your spouse withdraws the funds at retirement, your spouse will be taxed at their marginal tax rate. The most advantageous scenario for a Spousal RRSP occurs when the plan holder would otherwise have little retirement income, while the contributing spouse would have a significant amount of retirement income. Contributions you make to a Spousal RRSP reduce your contribution room, not that of your spouse.

The use of Spousal RRSPs as an Income Splitting tool may still be recommended despite the opportunities created by pension Income Splitting (as discussed on page 3), since Spousal RRSPs will allow for Income Splitting prior to age 65. In addition, a Spousal RRSP provides a further opportunity to increase the amount of Income Splitting beyond the 50 per cent limitation provided by the pension Income Splitting rules.

If you are over age 71 and have “earned income” that has created new RRSP contribution room, you can still contribute to a Spousal RRSP as long as your spouse is 71 years or younger – even though you can no longer contribute to an RRSP for yourself.

Leverage your Tax-Free Savings Account

Introduced in 2009, the TFSA is a general-purpose, tax-efficient savings vehicle that has been hailed as the most important individual savings vehicle since the introduction of the RRSP. Because of its flexibility, it complements other existing registered savings plans for retirement and education. The annual TFSA contribution limit for 2024 is $7,000, and is indexed for inflation (in $500 increments) for future years. Any unused contribution room can be carried forward from a previous year for use in future years. Accordingly, if you do not already have a TFSA, you may be eligible to contribute up to $95,000 ($5,000 for 2009 to 2012, $5,500 for 2013 and 2014, $10,000 for 2015, $5,500 for 2016 to 2018, $6,000 for 2019 to 2022, $6,500 for 2023 and $7,000 for 2024), if you were at least 18 years of age in 2009 and have been a Canadian resident since then. Contributions are not deductible for tax purposes; however, all income and capital gains earned in the account grow tax-free. All withdrawals from the TFSA (including income and capital gains) are received tax-free. In addition, the amount of the withdrawal will increase your TFSA carry-forward contribution room in the following year. A TFSA is beneficial for many investors and for many different reasons, including saving for short-term purchases such as an automobile or saving longer term for retirement. TFSAs can also be an effective Income Splitting tool. A higher-income spouse can give funds to the lower-income spouse or an adult child so that they can contribute to their own TFSA (subject to their personal TFSA contribution limits). As well, the attribution rules will not apply to income earned within the spouse’s (or adult child’s) TFSA. However, the Canada Revenue Agency takes the position that the attribution rules could apply when the funds gifted to contribute to a TFSA are subsequently withdrawn (i.e., where future income and/or capital gains are realized on funds withdrawn that are subsequently re-invested outside of the TFSA).

For older investors, TFSAs provide a tax-efficient means of investing – particularly beyond the age of 71 when they are no longer eligible to contribute to their own RRSP. In addition, if retirees are required to take more income than they need from a RRIF, they can contribute the excess amounts to a TFSA (subject to their TFSA contribution limit) and continue to shelter future investment earnings from tax. Furthermore, any withdrawals from a TFSA will not affect the eligibility for Federal income-tested benefits and credits (such as Old Age Security or Guaranteed Income Supplements). Where possible, the TFSA should be used in conjunction with an RRSP and other tax-deferred savings plans, such as an RESP. However, where funds are limited, a TFSA may be an appropriate savings vehicle for individuals who have forgone RRSP contributions because of the limited benefit of a tax deduction at low marginal tax rates. For others in a higher marginal tax bracket, a tax refund resulting from an RRSP contribution could be used to fund a contribution to a TFSA. Otherwise, the benefit of contributing to an RRSP versus a TFSA will depend largely on your tax rate at the time of contribution and at the time of withdrawal, upon retirement. Generally, an RRSP contribution will be more beneficial where the individual is in a higher tax bracket when contributing than expected when drawing upon the RRSP funds at retirement (including the possible clawback of any government benefits). However, there is no “one-size fits all” rule and each situation should be considered individually. The types of investments eligible for a TFSA are very similar to those investments eligible to be held within an RRSP. Similar to an RRSP, because of the tax-free nature of a TFSA, income that would otherwise be taxed at high rates outside a registered account, such as interest income, would be appropriate for a TFSA. Investments that may generate capital losses may not be appropriate for a TFSA since capital losses realized within a TFSA will have no tax benefit. However, ultimately the choice of specific investments in a TFSA will be unique to the investor, depending on such factors as their income needs, the investment time frame and their investment goals, tolerance for risk, and overall investment strategy.

Tip 4: Donate Appreciated Securities

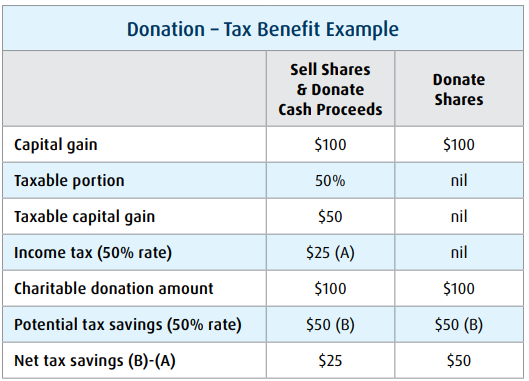

The benefits of making a charitable donation are countless – from helping those in need to the personal satisfaction we feel when giving something back to a cause we feel passionate about. With proper planning, you can also reduce your income tax liability and maximize the value of your donation. To optimize the tax benefit of making a charitable gift, a donation of qualifying publicly-traded securities may be preferred over a cash donation of equal value, particularly in cases where you have already decided to dispose of the securities during the year The fair market value of securities donated to charity will reduce your taxes through a charitable donation tax credit. For donations made after 2015 that exceed $200, the calculation of the Federal charitable donation tax credit will allow higher income donors to claim a Federal tax credit at a rate of 33 per cent (versus 29 per cent). This is only on the portion of donations made from income that is subject to the 33 per cent top marginal tax rate that originally came into effect in 2016. When combined with the provincial donation tax credit, the tax savings can approximate 50 per cent of the value of the donation (depending on your province of residence). A donation of securities is considered a disposition for tax purposes. If the security donated has appreciated in value since its purchase, you may incur a tax liability on the accrued capital gain. However, because of a special tax incentive to benefit those who donate appreciated qualified securities to charity, the capital gain inclusion rate on the donated securities is nil instead of the normal 50 per cent that would otherwise apply. The tax benefit realized as a result of this incentive can be significant. Qualified securities include mutual funds and shares, debt obligations or rights listed on a designated Canadian, or an international stock exchange. The following example illustrates the value of a charitable donation when the property donated is a qualified security, versus the cash proceeds from a sale of the security.

This example assumes the fair market value of the security is $100 and the adjusted cost base is nil (such as shares received from an insurance demutualization). It also assumes the individual is subject to the top tax bracket, has sufficient other income to avoid the annual limit on donation claims of 75 per cent of net income, and that other donations of at least $200 have been made in the year.

It should be noted that the tax benefits associated with this strategy may be restricted when flow-through securities are donated to charity. For more information, please ask your BMO Private Wealth professional for a copy of our publication, Donating Appreciated Securities and consult with your tax advisor.

Tip 5: Use Registered Plans to Save for Children’s Educational Needs and More

The increasing cost of post-secondary education has many parents and guardians concerned. To assist them in saving for a child’s education, the government provides the Canada Education Savings Grant (“CESG”), which applies to certain contributions made to Registered Education Savings Plans (“RESPs”). These grants, combined with the ability of the contributor to access the accumulated income in the RESP if not used by the beneficiary for education expenses, make RESPs a very attractive vehicle to fund your children or grandchildren’s post-secondary education. Contributions to an RESP are not tax deductible. However, the income from investments in an RESP (including the income from investments purchased with the CESG) is tax-sheltered provided it remains in the plan. RESP withdrawals to pay education expenses from accumulated income and the CESG will be taxable in the beneficiary’s hands at their marginal tax rate. There have been several enhancements to RESPs since their introduction. In particular, the annual contribution limit of an RESP was eliminated (which was previously $4,000 per beneficiary), and the lifetime contribution limit for each beneficiary was increased to $50,000 (from $42,000). More recently, greater flexibility for RESPs was provided by effectively extending the potential lifetime of RESPs by an additional 10 years, and allowing certain transfers amongst RESP plans for siblings, without triggering penalties or the repayment of CESGs. Generally, on the first $2,500 of annual RESP contributions for children up to the year they turn age 17, the Federal government will contribute an additional 20 per cent directly to the RESP, for a maximum CESG of $500 available each year (i.e., 20 per cent of $2,500), up to the maximum lifetime CESG of $7,200. If no contribution is made during the year, the CESG contribution room is carried forward. However, despite the elimination of the annual RESP contribution limits, the maximum CESG that can be received in a year from current and prior years’ unused grants is restricted to $1,000. A TFSA (discussed previously) provides another source of funding for a child’s educational needs and more. Although a TFSA cannot be established for a child under 18, due to the flexibility of the TFSA it is possible for a parent to direct their TFSA savings towards the funding of their child’s education. However, parents should first consider using RESPs to save for their child’s education to maximize the available CESGs and other government incentives that may be available for each child, particularly where it is expected that their child(ren) will pursue post-secondary education. Thereafter, if additional educational savings are required, the TFSA could be used as a supplement. It is also worth noting that once a child turns 18, they will generate TFSA room which will enable them to make contributions to their own TFSA (if they have reached the age of majority), which can be funded by parents without attribution. Thereafter, the TFSA assets can be used by the child for education or any other purpose.

Registered Disability Savings Plans

For individuals with disabilities, a tax-deferred investment savings vehicle similar to the RESP was introduced several years ago. The Registered Disability Savings Plan (“RDSP”) is a registered savings plan intended to help parents and others save for the long-term financial security of persons with severe or prolonged disabilities who are eligible for the Disability Tax Credit. Contributions up to a lifetime maximum of $200,000 per beneficiary can be made to an RDSP until the end of the year in which the beneficiary with disabilities turns 59, with no annual limit. Contributions are not tax deductible; however, any investment earnings that accrue within the plan grow on a tax-deferred basis. When earnings are withdrawn as part of a disability assistance payment, they are taxable in the hands of the beneficiary. Canada Disability Savings Bonds (“CDSB”) and Canada Disability Savings Grants (“CDSG”), up to annual and lifetime limits, can be received in an RDSP from the Federal government depending on family income.

Since the introduction of RDSPs in 2008, there have been many subsequent enhancements, including: the 10-year carryforward of CDSB and CDSG entitlements; the possible roll-over of RESP investment income to RDSPs; increased flexibility on withdrawals for beneficiaries with a shortened life expectancy; and the extension of the existing RRSP/RRIF roll-over rules to allow the roll-over of a deceased’s RRSP/ RRIF proceeds to the RDSP of a financially dependant child.

Speak to your BMO Private Wealth professional if you or members of your family are living with disabilities to understand more about these plans.

Tip 6: Use Borrowed Funds to Invest

Generally, interest expenses are deductible for tax purposes if the funds are borrowed for the purpose of earning income from a business or an investment vehicle, both initially and on an ongoing basis. Interest on borrowed funds that are used only to generate a capital gain is generally not deductible. Consider paying down non-deductible personal debts (such as RRSP loans, mortgages on home purchases and credit card balances) before paying down investment-related debt. For more information, ask your BMO Private Wealth professional for a copy of our publication, Leveraged Investment Strategies and Interest Deductibility, and speak to your tax advisor about the appropriate structuring of your particular investment strategy to achieve interest deductibility.

Tip 7: Reduce Tax for Your Estate

Your estate plan can accommodate a number of tax-saving strategies to reduce or defer the amount of tax payable by your estate and maximize the amount available to your heirs.

Use a trust to split investment income

If your beneficiaries are likely to invest their inheritance, it may be possible to protect your assets and reduce tax on investment income by using trusts created in your Will – called “testamentary” trusts. Similar to trusts created during your lifetime (“inter-vivos” trusts), as of 2016 any income retained in a testamentary trust will be taxed at the top marginal tax rates. However, two exceptions to the imposition of the flat top tax rate apply as follows:

• During the first 36 months following death, a deceased individual’s unadministered estate may be eligible for the graduated tax rates, provided the executor does not distribute the estate assets during this period, if so permitted under the terms of the Will (defined as a “graduated rate estate”).

• Graduated marginal tax rates continue to apply for a certain testamentary trust (defined as a “Qualified Disability Trust”) if established for a beneficiary who is eligible for the Federal Disability Tax Credit.

Although these changes eliminated access to the graduated tax rates on income retained and taxed within all existing and future testamentary trusts; trusts created in your Will, such as a trust for each child’s family, may still provide Income Splitting opportunities since they can be used to “sprinkle” income on a discretionary basis to family members in the lower tax brackets. In addition, testamentary trusts offer many other benefits (including control and protection), such that they will continue to be an important consideration in tax and estate planning. Because of the significance of these changes, it is important to consult with your tax and legal advisors to determine any impact to your existing Wills and estate plan, as well as any existing trusts established by you or your family members.

Name a beneficiary for your RRSP, RRIF or TFSA

The value of an RRSP or RRIF is included in the tax return of the annuitant in the year of death. If the beneficiary is your surviving spouse or a financially dependent child or grandchild, your estate will generally not be taxable on the proceeds from the plan. Instead, the beneficiary will include the proceeds in their income. Your surviving spouse can defer the tax on the proceeds if the funds are rolled into your spouse’s own RRSP or RRIF. Taxes can also be deferred if the beneficiary is a financially dependent child or grandchild who is a minor or has a disability (if under age 18, an annuity payable to age 18 is available; if individual is financially dependent and has a disability, a roll-over to the beneficiary’s own plan is available).

If any of these roll-overs are not available, the fair market value of the investments in the RRSP/RRIF at the time of death is generally included in the final tax return of the deceased. If the RRSP/RRIF investments have increased in value from the time between the annuitant’s death and the distribution to the beneficiary, the amount of the increase is generally included in the beneficiary’s income. On the other hand, the amount of any post-death decrease in the value of the RRSP/RRIF can be carried back and deducted against the deceased annuitant’s year of death income inclusion.

Subsequent to the introduction of the TFSA, most provinces introduced legislation also allowing beneficiary designations for TFSAs. Please note: Quebec does not allow the ability to name a direct beneficiary for an RRSP, RRIF or TFSA in the contract itself, instead a beneficiary can only be appointed in a Will. Where the TFSA holder designates a beneficiary (or beneficiaries), upon the death of the account holder the proceeds of the TFSA will be paid out to the beneficiary (or beneficiaries), and the TFSA will be closed. No tax will be payable by the deceased’s estate in respect of the TFSA, and the fair market value of the TFSA at death will be received tax free by the beneficiary; however, any income or growth post-death is taxable to the beneficiary.

A surviving spouse beneficiary has the ability to transfer the TFSA value at date of death to their TFSA (considered an “exempt contribution”), but to the extent that there has been any appreciation post-death, they would need sufficient contribution room to transfer this increase to their own TFSA. Many of these complexities are not applicable where a spouse is named as the “successor holder.” It is usually recommended that spouses are named as “successor holders” of TFSAs instead of beneficiaries, although generally probate fees (where applicable) will not apply in either case where a TFSA successor holder or beneficiary has been named.

Where the TFSA is not transferred to a surviving spouse, as previously stated, the fair market value of the TFSA at death would be received tax-free, but any income or growth post-death is taxable to the beneficiary. To the extent that the beneficiary has sufficient contribution room in their own TFSA, they would be able to transfer some or all of the inherited TFSA assets to their own TFSA, once the beneficiary has actually received the distribution from the deceased’s TFSA. Assets not transferred to the beneficiary’s TFSA will remain in the beneficiary’s non-registered account and any income thereon will be subject to future taxation. For TFSA holders without spouses, naming someone as a beneficiary can provide a means of avoiding probate fees on the fair market value of the TFSA (where applicable), but in some situations it may be desirable to have the assets pass through the Will to facilitate estate planning, notwithstanding the cost of obtaining probate. Ultimately, you should consult with your estate professional for confirmation of the appropriate designation on all of your registered plans in the context of your overall estate plan.

Defer capital gains

For non-registered accounts, capital gains that have not been realized during your lifetime are taxable to your estate upon death. However, if your investments are inherited by your surviving spouse (or a qualifying spousal trust), the tax on accrued capital gains can be deferred until the earlier of the time the investment is actually sold, or until the death of your surviving spouse. In some circumstances, subject to the terms of your Will, your executor may elect to realize a capital gain or loss on some, or all, of the property left to your spouse. For example, it may be beneficial to realize a capital gain sufficient enough to offset any unused losses carried forward in the year of death, and your spouse will inherit the higher cost base. Alternatively, a realized capital loss may be available to offset any income, not just capital gains, in the year of death or the immediately preceding year.

Charitable bequests

The charitable donation tax credit is generally subject to an annual limit of 75 per cent of net income. However, for donations made in the year of death the credit limitation is increased to 100 per cent of the deceased’s net income and any donations that cannot be claimed in the year of death can be claimed in the deceased’s prior year tax return, also up to 100 per cent of net income in that year.

Please note: The above 75 per cent limitation does not apply for 2016 and subsequent taxation years in calculating the qualifying Quebec provincial donation tax credit. The tax legislation allows additional flexibility in the tax treatment of charitable donations in the context of a death occurring after 2015. Specifically, a donation made by Will and designated donations (i.e., where an individual designates a qualified donee as a beneficiary under an RRSP, RRIF, TFSA or life insurance policy) is no longer deemed to have been made immediately before death, as was the case under previous legislation. Instead, these donation bequests are deemed to have been made by the estate at the time the specific property is donated to the qualifying donee. As a result, further planning opportunities exist for certain qualifying estates. Where applicable, estate trustees have additional flexibility to apply the donation tax credit, resulting from donations made during the first 36 months of an unadministered estate, to:

i. the taxation year of the estate in which the donation is made;

ii. an earlier taxation year of the estate; or

iii. the last two taxation years of the deceased individual.

Further amendments have added additional flexibility to apply a donation to income of the estate in the year of donation or the last two taxation years of the deceased, where the donation is made within 60 months of death by a (former) graduated rate estate.

Please consult with your tax and estate professionals should you wish to review the possible tax implications and benefits of any charitable bequest strategy within your existing estate plan.

Tip 8: Consider U.S. Estate Tax Implications if You Own

U.S. Investments Investing in foreign assets, such as U.S. securities, provides an opportunity for diversification. However, U.S. estate tax could be a concern if you are a Canadian who owns U.S. property at death. The estate of a Canadian is potentially subject to U.S. estate tax if the value of U.S. property owned personally at death exceeds US$60,000, and the value of worldwide assets exceeds the Federal estate and gift tax exemption amount of $13.61 million for deaths in 2024. The increased exemption (adjusted for inflation) is effective until 2025; however in 2026 the exemption is scheduled to revert to US$5million, adjusted for inflation.

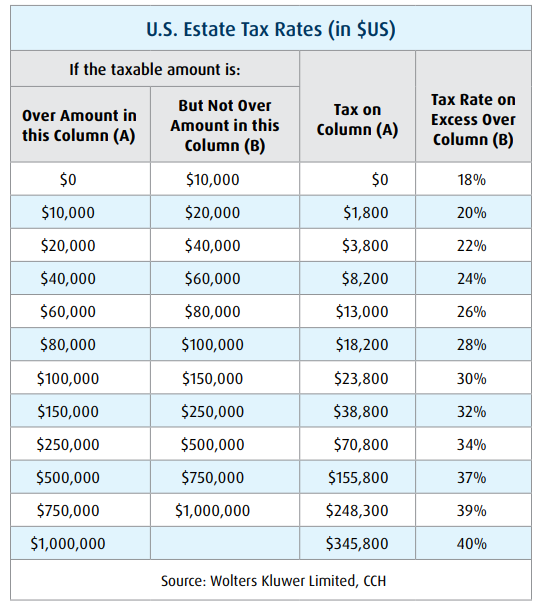

As shown in the table on the following page, U.S. estate tax generally escalates as the value of the estate increases. U.S. estate tax rates start at 18 per cent and increase to a maximum of 40 per cent. U.S. taxable property includes U.S. real estate, shares of U.S. corporations, many U.S. bonds and debts of a U.S. issuer, even if the investment is held in an RRSP, RRIF or TFSA. Canadian mutual funds that invest in U.S. securities or American Depository Receipts (“ADRs”) are generally not subject to U.S. estate tax. In Canada, estates are subject to Canadian income tax on accrued gains on all capital property owned upon death, including any U.S. taxable property (unless the property is left to a spouse or qualifying spousal trust). This means that your U.S. taxable property could attract U.S. estate tax, but it may also be subject to Canadian capital gains tax.

However, relief is available to reduce the adverse effects of U.S. estate tax imposed on Canadians in certain circumstances. The tax treaty (“the Treaty”) between Canada and the U.S., together with Canadian tax rules, may:

• Eliminate U.S. estate tax for small estates with a worldwide value below the amount covered by the unified credit (US$13.61 million for 2024 and indexed for inflation in future years);

• Provide Canadians with access – but only on a pro-rated basis – to the same unified credit and marital credit available to U.S. citizens to reduce U.S. estate tax; and

• Allow U.S. estate tax paid as a foreign tax credit, but generally only against Canadian Federal capital gains tax payable on the U.S. property. Previous changes to the treaty extended the possible credit of U.S. estate tax against Canadian income tax payable at death on RRSPs, RRIFs and stock options.

These provisions may not apply to all Canadians owning U.S. taxable property. In particular, Canadians who are U.S. citizens are subject to different regulations. Investors should be aware that tax planning opportunities are available in order to minimize the exposure to U.S. estate tax.

For more information, please ask your BMO Private Wealth professional for a copy of our publication, U.S. Estate Tax for Canadians and Tax and Estate Consequences of Investing in U.S. Securities.

Finally, investors are reminded of the CRA requirement to disclose their foreign investments annually on Form T1135 (Foreign Income Verification Statement), if the aggregate cost of the non-registered foreign property exceeds CDN$100,000 at any time during the year. For more information on this CRA reporting requirement, including the simplified Form T1135 reporting method available, where the aggregate cost of foreign securities held was less than CDN$250,000 throughout the year (but exceeded CDN$100,000), please ask for a copy of our publication, The CRA’s Foreign Reporting Requirements.

Tip 9: Recent Housing Initiatives

The Federal government has recently introduced a number of new measures focusing on housing, including the following:

Tax-free First Home Savings Account

Introduced in 2023, the tax-free First Home Savings Account (“FHSA”) is a new registered savings account allowing first-time home buyers to save up to $40,000 towards the purchase of their first home. Combining hallmark attributes of RRSPs and TFSAs, contributions made into the FHSA are tax-deductible and income earned in an FHSA is not subject to tax. Qualifying withdrawals (including investment income) from the FHSA, to purchase a first home, will be non-taxable. First-time homeowners, who are at least 18 years of age or older, are eligible to open an FHSA, subject to an annual contribution limit of $8,000, with a lifetime limit of $40,000. However, unlike an RRSP, contributions to an FHSA must be made before the end of the calendar year to provide a current year deduction; eligible first-time home buyers should therefore consider opening an FHSA and making a contribution before the end of 2024. For further information and planning considerations, read our First Home Savings Account publication.

Multigenerational Home Renovation Tax Credit

For qualifying expenses paid after 2022, a new (refundable) Federal Multigenerational Home Renovation Tax Credit allows families to claim up to $7,500 (i.e., 15 per cent of up to $50,000 in eligible renovation and construction costs) for constructing a secondary suite for a senior or disabled (adult) relative.

Residential Property Flipping Rule

For sales of any residential properties after 2022, homeowners should be aware of new rules enacted recently that will tax the sale of a property that is held for less than 12 months as business income (and ineligible for the Principal Residence Exemption). However, exemptions apply for Canadians who sell their home due to certain life circumstances, such as a death, disability, the birth of a child, a new job, or a divorce.

Underused Housing Tax

The Federal government recently introduced the Underused Housing Tax (“UHT”), which imposes a national one per cent annual tax on the value of non-resident, non-Canadian-owned vacant or underused residential real estate in Canada. Canadian property owners, including private corporations, certain trustees, and partners, may have a filing obligation, even if no tax is owed. The deadline for the 2022 UHT returns was initially May 1, 2023, however the CRA subsequently announced that the application of penalties and interest for late filing and payment for 2022 UHT returns will be waived if the 2022 returns are filed and taxes paid by April 30, 2024 (which is also the deadline for 2023 UHT returns).

Tip 10: Year-End Tax Planning

Tax planning should be a year-long event; however, here are some year-end tips to help reduce income tax costs for you and your family and an overview of some important recent tax developments.

Important dates to remember

December 15, 2024

Due date for final income tax instalment payments for individuals. Consider the impact of investment income on quarterly tax instalments to avoid non-deductible arrears, interest and penalties.

December 30, 2024

Estimated last buy/sell date for securities to settle in the calendar year (based on the updated settlement cycle of trade date plus one effective in May 2024). Review investment portfolios to consider the sale of securities with accrued losses before the end of the year to offset capital gains realized in the year, or in the three previous taxation years (if net capital loss created in current year). Watch the superficial loss rules that can deny the capital loss on the sale of an investment if repurchased within 30 days by you, your spouse or other affiliated entity. Ask your BMO Private Wealth professional for a copy of our publication, Understanding Capital Losses for more information on this strategy.

January 30, 2025

Last day to pay annual interest on family loans to avoid income attribution (see page 3).

March 1, 2025

Last day to make a 2024 RRSP contribution, unless you turned age 71 in 2024.

Other planning considerations

Conversion of your RRSP into a RRIF

Are you turning 71 in 2024?

• You must wind-up your RRSP by the end of the year in which you turn 71, so consider making a final RRSP contribution to the extent you have any unused RRSP contribution room by December 31, 2024.

Children

• File a tax return for children with “earned income” to start accumulating RRSP contribution room.

• Start saving for your child’s education – contribute to an RESP and you may be eligible for a government grant (see page 8).

• Keep in mind the maximum dollar amounts that can be claimed under the Child Care Expense deduction are generally $8,000 per child under age seven, and $5,000 per child aged seven to 16.

Medical expenses

• Combine medical expenses for you and your family on one income tax return and choose the 12-month period ending in the year that contains the most expenses. Donations

• Donate appreciated securities instead of cash for enhanced tax savings (see page 7).

• Make all charitable donations by December 31 (including donations planned for early next year).

• Combine all charitable donations for you and your spouse and claim on one income tax return for maximum tax savings.

• Be aware that for donations made after 2015 that exceed $200, calculation of the Federal charitable donation tax credit will allow higher income donors to claim a Federal tax credit at a rate of 33 per cent (versus 29 per cent), but only on the portion of donations made from income that is subject to the 33 per cent top marginal tax rate that originally came into effect in 2016. When combined with the provincial donation tax credit, the tax savings can approximate 50 per cent of the value of the donation (depending on your province of residence).

Canada Training Credit

The Canada Training Credit was recently introduced to address barriers to professional development for working Canadians. This new refundable tax credit aims to provide financial support to help cover up to half of eligible tuition and fees associated with training. Eligible individuals between the ages of 25 to 64 can accumulate $250 each year in a notional account, to a lifetime limit of $5,000.

Employee home office expenses

Eligible employees who seek to claim home office expenses for 2023 must now use the detailed method, which requires a completed Form T2200, Declaration of Conditions of Employment, signed by their employer (Form TP-64.3, General Employment Conditions for Quebec provincial tax purposes). Employees who worked from home in 2023 are generally eligible to deduct home office expenses that were directly related to their work if they were required to work from home and worked from a home office more than 50% of the time for a period of at least four consecutive weeks in 2023.

For 2023, if an employee has voluntarily entered into a formal telework arrangement with their employer, CRA will consider the employee to have been required to work from home.

Notably, the temporary flat rate method, which was available for 2020, 2021 and 2022, will no longer apply for the 2023 tax year. This simplified method previously allowed employees (with modest expenses) to claim a flat-rate deduction of two dollars for each day they worked at home, up to a maximum of $500, without the need to track detailed expenses.

Employee stock options

Recently-enacted legislation restricts Canada’s beneficial employee stock option tax treatment for employee stock options granted on or after July 1, 2021. Specifically, a $200,000 annual limit (per vesting year) applies on certain employee stock option grants (based on the fair market value of the underlying shares at the time the options are granted) that can receive tax-preferred treatment under the employee stock option tax rules (i.e., 50 per cent taxable). Employee stock options above the limit are subject to the new employee stock option tax rules (i.e., full taxation of the employment benefit).

Employee stock options granted by Canadian-controlled private corporations (“CCPCs”) are not subject to the new limit. In addition, in recognition of the fact that some non-CCPCs could be start-ups, emerging or scale-up companies, non-CCPC employers with annual gross revenues of $500 million or less are also not subject to the new limit.

Given the significant potential impact of these recent changes, affected individuals and employers should consult with their tax advisors to determine the specific tax implications in their particular situation.

Luxury Tax

The 2021 Federal Budget announced the introduction of a new a tax on the sales, for personal use, of luxury cars and personal aircraft with a retail sales price over $100,000, and on boats over $250,000. This Luxury Tax, which took effect on September 1, 2022, is calculated at the lesser of 20 per cent of the value above the relevant threshold or 10 per cent of the full value of the luxury car, boat, or personal aircraft.

Alternative Minimum Tax

As initially highlighted in its 2021 Election Platform, the Federal Liberal government is seeking to ensure that high income earners pay income tax at a rate of at least 15 per cent each year and cannot artificially reduce their taxable income through excessive use of deductions or credits. Although the current Alternative Minimum Tax (“AMT”) regime has been in place since 1986, the government proposed a new minimum tax regime, the details of which were released in the 2023 Federal Budget. Key design features of the new AMT regime proposed include broadening the AMT base, further limiting tax preference items (i.e., exemptions, deductions and credits) and increasing the AMT tax rate. Many high-income individuals (especially those with substantial capital gain or dividend income) claiming significant deductions and credits (including charitable donations) and many Family Trusts may be affected by these amendments, which are proposed to take effect in 2024. Investors with significant gains/losses should also note that the proposals will allow only 50 per cent of carryover losses applied for AMT purposes, whereas gains will be fully taxable. Review our BMO publications, 2023 Federal Budget Review and Proposed Changes to the AMT Could Complicate Charitable Giving and speak with your tax advisor for assistance regarding your personal situation, to determine the possible application of AMT.

Conclusion

This publication is neither a comprehensive review of the subject matter covered nor a substitute for specific professional tax advice. Therefore, the tax strategies contained in this publication may or may not be appropriate for your situation. You are encouraged to consult with an independent tax professional to confirm the anticipated implications to your particular situation of the current tax legislation in developing and implementing any tax strategies.

BMO Private Wealth is a brand name for a business group consisting of Bank of Montreal and certain of its affiliates in providing private wealth management products and services. Not all products and services are offered by all legal entities within BMO Private Wealth. Banking services are offered through Bank of Montreal. Investment management, wealth planning, tax planning, philanthropy planning services are offered through BMO Nesbitt Burns Inc. and BMO Private Investment Counsel Inc. If you are already a client of BMO Nesbitt Burns Inc., please contact your Investment Advisor for more information. Estate, trust, and custodial services are offered through BMO Trust Company. BMO Private Wealth legal entities do not offer tax advice. BMO Trust Company and BMO Bank of Montreal are Members of CDIC.

® Registered trademark of Bank of Montreal, used under license.